Jen Bowden, Scoop: Writer Catherine Cole uses her full powers of observation to craft these realistic, honest narrative nuggets of humanity.

It’s often the case that a collection of short stories will feature a number of tales that hit the mark, but also ones that miss it by a mile. Catherine Cole’s collection Seabirds Crying in the Harbour Dark is very much lacking the ‘miss’, with each tale so expertly crafted that the author’s talent for observing the subtle nuances of human life is almost intimidating. Read on...

Kerryn Goldsworthy, The Canberra Times: This is a short-story collection of great substance and style. There is variation in setting and character but a couple of themes draw the stories together into a cohesive whole, as does the "discontinuous narrative" effect of reencountering some characters in different stories.

Catherine Cole's writing is beautiful, full of intelligence and grace, and always suggestively understated. Most of these stories feature, or come back to, the idea of the beach and the ocean. Linked to that is a recurring preoccupation with the idea of home, which again emerges in a variety of ways. Read on...

Matt Condon, The Sun Herald: How refreshing to read a novel that deals with up-to-the minute issues, complete with contemporary street, hotel, cafe, bar and personality references, and all wrapped up in the mantle of a thriller. Cole, a long-time resident of Balmain, has made the turf her own in Dry Dock. Nicola Sharpe is a private investigator, looking into the case of the beautiful Selina Bower, city investor, who is being stalked.

Enter Kevin O'Leary, old friend of Sharpe's father, who worked as a sheet metal worker. Once a powerful union voice, O'Leary is threatened after a council meeting. Then things start to go awry. Written with clarity and pace, this is a fine first novel that also laments the loss of suburban values.

Stuart Coupe, The Sydney Morning Herald: Cathy Cole's Dry Dock is set around the formerly working-class and now increasingly yuppified inner-Sydney suburb of Balmain. As with the work of Marele Day, Jon Cleary and Peter Corris, the urban environment of Sydney is very much at the core of this novel. Private investigator Nicola Sharpe finds herself embroiled in perceived union corruption and suspect goings-on involving building developments in Balmain...

Much of Dry Dock is a homage to "old" Balmain, for which Sharpe remains intensely loyal and nostalgic: When the suburb gentrified in the eighties, a generation of Balmain's young moved on to houses in the suburbs. Their parents stayed at the flats. They were the grey-haired players of the pokies at the Balmain Leagues Club, the men you saw fishing off the wharf, the old ladies who needed a hand at the supermarket.

Remembrance of days gone by remains a constant theme throughout the novel, and the suburb at the centre of Dry Dock is little different from dozens of others in cities and towns around Australia: I couldn't stop myself thinking about Balmain and the people who live in the suburb. The mix of old and new Balmain going about their business, the school kids and teachers at Birchgrove Primary. Ferry passengers on their way to the city. Labourers and lawyers. I wanted to talk to Mary in the cake shop as she sprinkled hundreds and thousands on top of a pink iced jam sponge. Hear Lucio talk about what Balmain was like when he opened his delicatessen in 1956. Sit at the bar in the Unity Hall and listen to the old men and women playing trad jazz. …a highly entertaining and well-sustained novel from a newcomer.

Graeme Blundell, The Weekend Australian: Reading Cathy Cole's Skin Deep makes it is clear why women writers choose crime over other literary models in order to explore political structures. And how, in a rocket ride of visibility, they have given the genre a new lease of life through the female voice, moving their private eyes from curiosity pieces to a kind of critical mass in the late 1980s.

Art fraud and corpses (some art-directed, some just dead), right- wing extremism, the human fallout of economic rationalism, a political landscape dominated by conservative hardliners into payback, mothers and their daughters, the effects of gentrification on the inner city -- these are some of the themes Cole juggles in Skin Deep. Her 180cm hero, Annie Lennox look-alike Nicola Sharpe, discovers the "pernicious smell of artist's oil paint" is as corrosive as air "wounded with smoke" from burning pyres of fallen leaves in inner-city Sydney backyards.

Sharpe, looking after her heart these days, is a welcome addition to the ranks of women detectives created in the past 20 years, those assertive and self-sufficient sleuths who have transcended generic codes and virtually rewritten the archetypal male detective from a feminist perspective. Skin Deep begins with a passionate kiss on the hottest Sydney night for 15 years, and the pressure -- climbing with the humidity - - builds to a final redemptive kiss after the bodies have piled up. Surer and tougher in style than in her debut novel, Dry Dock, Cole uses mordant social commentary to greater effect, resisting hyperbole, pastiche and the overdone, one-liner humour that bedevils many new crime novelists.

Debra Adelaide, The Sydney Morning Herald: Fans of Cole's first novel, Dry Dock, won't be disappointed by the next story involving Annie Lennox look-alike and medium-boiled PI Nicola Sharpe. Nicola is hired to keep an eye on Ella Davies, the student-activist daughter of a famous artist, but she learns there's more to the Davies family than meets the eye. The plot involves a couple of corpses notably a naked woman arranged like a pre-Raphaelite painting a missing young woman, fake paintings and fanatical right-wing politics.

All the right ingredients are here: images of the city as tawdry and corrupt (and most of its inhabitants not much better); a lone gumshoe with a beat-up car and handy police connections; vividly drawn locations from Balmain to Glebe and the Easter Show; and a snug love interest to compensate for all the meanness and grubbiness of the world of art fraud and political conspiracy.

Graeme Blundell, The Australian: Something for every armchair sleuth and mean streeter. Stylishly shifting between personal observation and critical commentary, Cole entertainingly lifts the lid on the dark world of crime fiction.

The Thrilling Detective: This academic monograph examines the continuing popularity of crime fiction and investigates its on-going relevance, ranging from socio-economic, feminist, moral and political concerns, but also gets down and dirty (and a lot more fun) when it looks into why some books work and some don't and the origin of the term "red herring." What might have been a dry, crusty read is enlivened by a breezy style, shaped no doubt by the author's own enthusiasm for the subject.

Gabrielle Lord: With insights gained from being both a crime writer and critic, Cathy Cole examines crime fiction entertainingly and thoroughly in this book.

Drusilla Modjeska, The Monthly: In its sure-footedness with language, The Grave at Thu Le echoes the modernism of Virginia Woolf, or more obviously Marguerite Duras, but it doesn't have Duras's self-absorption, or her slightly repellent self-referential eroticism. If there's an eroticism here it is for the place, an affirmation of the visible, elusive contemporary Hanoi, with the optimism of its young population – two-thirds of whom were born after the war ended in 1975 – working its own curious blend of the global and the communist with ancient traces of the dragon taking flight.

(Cole) writes without the guilt that has been so debilitating to our political and intellectual culture. She doesn't engage with debates about guilt or blame, neither fending them off nor joining the chorus of mea culpa. She brings an awareness to attitudes of mind that Australian readers will recognise, even if the French–Vietnamese history is unfamiliar. It is Cole's probing of nostalgia as a response to the discomforts and displacements of a post-modern, post-colonial world that is the challenge of The Grave at Thu Le – and its success.

Jane McLean, Business Traveller Asia: The Grave at Thu Le meanders slowly, steadily, like a Sunday stroll through a tree-filled park. There are no thrills, no spills, no great revelations, but rather a touching narrative set in a city soaked in a fascinating, yet sometimes, turbulent history.

Delia Falconer, The Australian: By creating a shimmering and enigmatic narrative surface, Cole perhaps mimics the dangerous delicacy with which the D'anyers family has repressed and aestheticised its own colonialism. This sense of elusiveness and fragmentation is strikingly reinforced by the texture of Cole's book.

Mark Thomas, The Canberra Times: The book is sentimental but not cloying; affectionate, but not indulgent. Cole's overall effect is one of collage, of impressions superimposed on top of each other, of memories juxtaposed with emotions, of sensations experienced one after another to form a palimpsest. Her texturing of text is intensely rendered and most accomplished.

Peter Pierce, The Sydney Morning Herald: Cleverly crossing boundaries of genre, Cole's book is arresting from its first moment until its plangent last words.

Christopher Bantick, The Hobart Mercury: THIS is a book that is both subtle and deeply poignant. A. D. Hope, arguably Australia's greatest poet last century, died in 2000. In The Poet Who Forgot, Catherine Cole presents a portrait of a man she corresponded with for almost two decades. What stopped their letters was not Hope's death but his advancing dementia during the 1990s….What is evident in Cole's recollections of her friend and mentor Alec Hope is a man of effusive generosity. But while the book gives an insight into the nature of their correspondence and the relationship that developed from it, Cole has reflected on how Hope essentially changed her as both a writer and a person.

The book, palpably affectionate in its rendering of Hope, is not panegyrical in tone; Cole avoids eulogising…. There is much in this book to enlighten readers about Hope's considerable life. But what lasts is the gift Hope gave Cole. It is how she came to understand herself and through that to discover a kind of love for a man who wrote poems for 50 years and then, she says, 'forgot'.

Kevin Hart, The Australian: Catherine Cole met the same man I had come to love a decade after I did, and her new book, The Poet Who Forgot, is a fond memoir of her mentor. In 1982, as an undergraduate, she wrote to Hope, whose poems she admired. He exemplified, she thought, the three attributes that Vladimir Nabokov deemed essential to a writer: 'storyteller, teacher, enchanter'. Hope replied to her letter with his usual hospitality, asking her to visit him if she should ever be in Canberra. And so began a lively correspondence, enriched by lunches and dinners spent talking of Louise Labe and W. B. Yeats, prefaced by whisky and lushly extended with red wine.

Geoff Page, The Canberra Times: The Poet Who Forgot certainly does do justice to the complexity and contradictions of a much-admired Australian poet who almost certainly will remain an important figure in our literature and, indeed, in world literature.

Victoria Laurie, The Australian: Writer Catherine Cole has done something too few of us do. She has taken time out to reflect deeply on a person who helped shape her career and who arguably changed her life.

Google Books: This book examines the ways in which dress 'performs' in a wide range of contemporary and historical literary texts. Essays by North American, European and Australian scholars explore the function of clothing within fictional narratives, including those of film, television and advertising.

The book provides a groundbreaking examination of the interconnected worlds of fashion and words, providing perspectives from socio-cultural, historical and theoretical readings of fashion and text-based communication. Covering a variety of genres and periods, Fashion in Fiction analyzes fashion's role within a range of creative media, exploring the many ways that dress communicates, disrupts and modulates meaning across different cultures and contexts.

Jessica Hemmings, Book Reviews: A loose historical organization has been applied to the order of the fourteen chapters. Appropriately, considering her significant contribution to this area of research, Hughes begins the collection with discussion of male dress in characters that inhabit the fiction of Balzac, Goethe and Thackeray and considers how dress can act as a marker of "rank and status writ large" (11). The remaining contributions consider narrative, fashion and fiction in a broad sense. For example, Sophia Errey writes of the "implied, but plotless, narrative" stylists' conjure with fashion photography (50).

Margaret Maynard focuses on Australian fashion photography. Catherine Harper considers her own personal narrative and the two garments she and her partner wore on the day of their civil partnership ceremony. Sarah Gilligan writes of masculinity and costume in the Matrix films and notes that a "radical shift has taken place in the representation of masculine identities within recent sci-fi and action cinema." Dagmar Venohr contributes the final essay of the book and in many ways the most abstract. Her stated "aim is to claim more bliss on the subtle textile in written texts" (165).

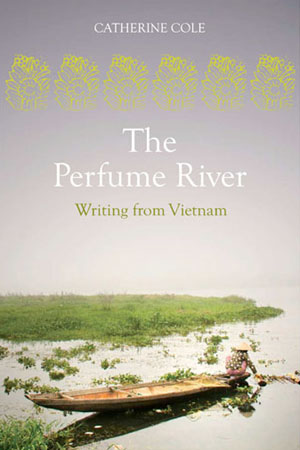

Geordie Williamson, The Australian: Attractively produced, carefully edited, and -- to my ignorant ear, at least -- often beautifully translated, The Perfume River is a labour of love that is a credit to all involved in its production. It reminds us of how correct Marcel Proust was, when he said that it is only through the agency of art that we leave our own selves and know what it is to be another. But the anthology also suggests a limit to the insights even the most thoughtful and talented Western observer can bring to an alien culture.

Its pages hint at a disquieting thought: contemporary capitalism might be as destructive to the warp and weave of Vietnamese society as communism ever was. And yet the best Vietnamese contributors manage a generosity toward the outside world that is humbling.

In Vietnam, it is said, no distinction is made between spirits of ancestors and those of strangers: both are accorded a place alongside the world of the living. Just as hospitality is extended, even to the shades of men who came to kill earlier generations, so too do its writers reach out, to a world that retains the power to do its own subtler kind of harm.

Sleep (UWA Publishing, 2019)

Better Reading: Exquisite. An Astounding Achievement

I read a lot of good books for work. Even great books. Just occasionally something truly special comes alone. Sleep by Catherine Cole is one such book. In a small London café, teenager 17-year-old Ruth, and elderly French artist, Harry, recognise something profound in each other.

They strike up a conversation that leads to regular meetings. A friendship is born. There are complications that come with this friendship, however this beautiful book is somewhat of a relief. It really is about human connection and a friendship... Read on...

Weekend Australian: Artful approach to mental health

When I first had small children, I used to say that all I wanted for them in life was to find a good job, a caring partner and to be happy. Simple. Or maybe not so simple —because that’s everything, isn’t it? It’s what we all hope for, and it’s not easy to find.

Life deals up bad cards from time to time: grief, loss and sadness are part of the journey. But how do we tackle difficult times? And how do we heal? These are questions explored by Catherine Cole in her latest novel, Sleep. Sleep is the story of Ruth, a young woman who has lost her mother, Monica, to mental illness.

For Ruth, as for most people who have faced traumatic loss, healing is difficult: there’s a heavy personal burden to deal with, as well as the impact of her mother’s illness on the family. Read on...

Be Careful What You Remember

Catherine Cole’s new novel Sleep revolves around an extended family of women and the ways in which they manage intergenerational trauma. The protagonist, Ruth, struggles with issues of abandonment. She has to deal with the trauma of her mother, Monica, which had been passed down to Monica through her father, a survivor of the Second World War. He returned from the war a troubled and restless...Read on...